- Home

- Simon Goddard

Ziggyology Page 7

Ziggyology Read online

Page 7

The first days of 1947 were perishing. A cruel winter had instigated a national fuel crisis with the government forced to seize control of the collieries. The coal shortage was bad enough to halt production at the EMI factory in Hayes, Peggy’s former wartime workplace. London staggered to a freezing halt as lorry drivers decided on an unofficial strike, causing a backlog of undelivered mail and animal carcasses, much to the despair of its still ration-couponed housewives.

On the afternoon of Tuesday 7 January, a fresh snow fell over the city. In Hammersmith, chattering jaws cowered for warmth inside the Gaumont Palace cinema to watch The Jolson Story – ‘a lifetime of supreme entertainment in a cavalcade of Technicolor music and song!’ In Westminster, a taxi skidded on the ice and killed a pram-pushing mother, while in Stockwell an 87-year-old man nearly died when he slipped after disembarking a double decker bus.

The streets were still sludgy on the morning of 8 January when, just after 9 o’clock, a brute half-masked in a blue handkerchief held up a bank on Gloucester Road, escaping with £163 and the stains from an inkwell launched at his head by a plucky cashier as he fled. At around the same time, across the river in Brixton, the son of Peggy and John was delivered in Stansfield Road. They named him David Robert Jones.

After his birth, the attendant midwife, a woman of evidently superstitious character, said something quite unexpected. ‘This child’s been on Earth before,’ she told Peggy. ‘It’s his eyes, they’re so knowing.’

The midwife was right. He had. The ideas yet to sparkle in the knowing eyes of Brixton-born David Jones were of ancient universal origin. But he, and he alone, would thread them into wild new ecstatic joys of pure being.

EIGHT

THE SOUND

THE YEAR 1947. Twenty-five years before Ziggy Stardust, whose human canvas fate had finally selected in the boy born David Jones. A canvas which now needed to be primed and stretched to the shape of the Starman by the gods of chance and circumstance. In 1947 those gods were already on his side.

That nativity Wednesday in January, in Brixton, the knowing eyes of the infant Bowie first squinted at the world with new-born dreams of domination, while over four thousand miles away a similar working-class fantasist lost in music, haircuts, flashy trousers and visions of lightning bolts, was waking up to his twelfth birthday in Tupelo, Mississippi. Another of history’s different boys. Whose conception was so seismic his father blacked out after the moment of climax. Whose birth was so biblical it was said that night there was a strange bluish glow in the sky around the moon. Who was delivered thirty-five minutes after a stillborn twin brother his parents named Jesse Garon. Who later wondered, ‘If my twin brother had lived, do you reckon the world could’ve handled two?’ Who always knew, regardless, Planet Earth was only ever big enough for one Elvis Presley.

At the age of twelve, Elvis was already strumming his first guitar, a present from his previous birthday, if initially something of a disappointment. He’d asked for a bicycle, a luxury beyond the means of his poor, God-fearing parents – a besotted, heavy-drinking mother and a desperate, undependable father who missed three crucial years of his son’s upbringing picking cotton on a chain gang as penance for doctoring a cheque he’d received in exchange for a pig. In his dad’s absence Elvis pined for a male role model, finding one in the comic strip adventures of a boy named Billy Batson who, with a single splutter of the magic word ‘Shazam!’, transformed himself into the adult superhero Captain Marvel. His impressionable young eyes were especially enamoured with Marvel’s costume: gold boots, a white cape and a red jumpsuit marked by a sharp, gold lightning flash.

Flashes of gold lightning were soon joined by the sound of rattling thunder thumping up the road to his Tupelo family home from Shake Rag, a nearby black housing project whose residents triumphed over daily dismay swinging a constant brickbat of rhythm and blues. For a boy on the cusp of adolescence his sneaks into Shake Rag offered a refuge from humdrum reality in a private Oz of alien music. The shrieking profanities from smoky juke joints and the liquor-stewed twangs of front-porch wailers singing the woes to befall them since they’d woken up that morning. Elvis heard and saw what those deafened and blinded by skin colour refused to. That the stark sound of Shake Rag was the same primeval roar and storm unleashed by Beethoven over a century earlier, fired in the post-war heat of the Mississippi Delta, a sound which set the metronome for the rest of his life. It took the genius of Beethoven to invent rock ’n’ roll, but the voice of Elvis Presley to sign its belated birth certificate.

True to his vocation as the first rock ’n’ roll superstar, the teenage Elvis understood his duty to stand out from the crowd – that pop music was all about the songs but, equally, the trousers. In his case, baggy black ones with pink piping down the side. When his family moved to Memphis it placed him in temptation’s way of the zoot suits, pink peg slacks, ruff shirts, white buck shoes, sideburns, pompadours and ducktails as worn by the black dandies of Beale Street. Elvis, pop’s original style magpie, reconstructed his wardrobe accordingly. In the corridors of Humes High School he was the solitary pink-clad pompadour punk bobbing amidst a disapproving sea of short back and sides. Even his gait was a source of fascination. ‘It was almost as if he was getting ready to draw a gun,’ recalled one of his few school friends. ‘It was weird.’ So Elvis bamboozled straight society, a weirdness of hips, lips, cotton and brilliantine oscillating an anomalous haze between white and black, male and female.

‘I DON’T SOUND like nobody.’

So the 18-year-old Elvis told Memphis Recording Service office manager Marion Keisker when he walked into their reception at 706 Union Avenue on the humid Saturday afternoon of 18 July 1953. The studio doubled as headquarters of Sun Records, the new venture of established R&B producer Sam Phillips who offered the public a $4 vanity service to make a one-off 78 r.p.m. acetate. Their slogan: ‘We record anything – anywhere – anytime.’

Well-worn rock ’n’ roll legend would plead Elvis went there to cut a record as a gift for his mother’s birthday – but that was another ten months away. In all likelihood he was just restless to hear himself on record. After Keisker set him up in front of the microphone, Elvis started strumming the same beat-up acoustic guitar he’d been dragging around since the age of eleven, opened his mouth and sang. ‘Whether skies are grey or blue, any place on Earth will do …’ He was right. He didn’t sound like nobody. Not on this planet.

The two songs Elvis recorded that day, ‘My Happiness’ and ‘That’s When Your Heartaches Begin’, were ballads. Keisker kept a copy of the songs and made a note of him in the studio log. ‘Good ballad singer. Hold.’ The following Monday Elvis returned to work cutting metal in a machinist’s shop and waited. And waited.

While destiny kept Elvis at bay, Sam Phillips continued to show an instinctive genius for pickaxing black R&B gold on early Sun singles by Rufus Thomas (‘Bear Cat’, ‘Tiger Man’), Little Junior Parker (‘Feelin’ Good’, ‘Mystery Train’) and the harmonic Tennessee State Penitentiary inmates calling themselves The Prisonaires (‘Just Walkin’ In The Rain’). Only occasionally did his Midas touch desert him. In early 1954 he gambled on white country singer Doug Poindexter and a Hank Williams-style spur-trembler called ‘Now She Cares No More’. The record flopped but a fleck of potential sparkled in the song’s co-writer Scotty Moore, guitarist with Poindexter’s backing band The Starlite Wranglers. Phillips sensed Moore’s keenness to create new music. Moore sensed Phillips’ ambitions for Sun to obliterate the racial barricades of the early-fifties American record industry. As Phillips supposedly confided to Keisker: ‘If I could find a white man who had the negro sound and the negro feel, I could make a billion dollars.’

It was such a discussion on Saturday 3 July 1954 – nineteen years to the death of Ziggy Stardust – that prompted Keisker to remind Phillips of the unusual dark haired ‘good ballad singer’ kid who’d now auditioned three times without any success. Moore was intrigued and asked Keisker if she still had his deta

ils. She did, though she’d misspelled the name ‘Elvis Pressley’. Moore laughed. ‘That sounds like something outta science fiction.’

Phillips was still undecided. He knew ‘there was something’ about the Presley boy’s voice but remained at odds where to channel it. Maybe, as Keisker suggested, Moore could help him find the answer. In the early hours of Tuesday 6 July, he did.

Moore had called Elvis, inviting him to join himself and Starlite Wrangler upright bass player Bill Black for a trial session at Phillips’ studio booked for seven o’clock on the evening of Monday 5 July. All three fumbled in the creative darkness for a song they all knew, settling on Ernest Tubbs’ country ballad ‘I Love You Because’, kicking it around for hours but making little impression on Phillips in the control room. Around midnight, the trio took a break, wondering whether they should call it a day and try again tomorrow. Until Elvis stood up with his guitar and began to sing …

FOUR THOUSAND MILES away, dawn had already broken over Clarence Road in Bromley, where seven-year-old David Jones and his family had since moved from Brixton. Perhaps at that very moment the boy stirred in his bed, opening his eyes just as Elvis Presley opened his mouth. The two sons of 8 January awaking half a world away from each another, one physically, the other spiritually.

In Bromley, David Jones yawned.

In Memphis, Elvis Presley yodelled.

‘Well, that’s all right, mama …’

PHILLIPS’ BRAIN SIZZLED between his ears in flamed amazement. The fidgety white ballad kid was singing a black juke joint favourite, ‘That’s All Right’, by Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup. Recorded in 1946, more recently it had been among the first singles issued in a brand new recording format: the 45 r.p.m. vinylite seven-inch single, the destined holy vessel of pop perfection marking the death of the shellac 78 which had carried the sounds of Holst and Hoagy Carmichael. The seven-inch was launched in early 1949 by the label RCA Victor, whose trademark flicked a lightning bolt on the tail of the ‘A’. To distinguish Crudup’s disc as part of their generic ‘blues and rhythm’ series, it was pressed in a special coloured vinyl, officially ‘cerise’ but in the cold light of day more ‘red hot red’.

As Elvis started hollering ‘That’s All Right’ Moore and Black followed his lead and jammed along. Phillips told them to stop so he could switch the microphones on and tape it properly. A few takes later, they listened back. Nobody knew exactly what they were hearing, only that it was ‘different’, ‘exciting’, ‘raw and ragged’. It was a white kid singing black blues attended by the giddy jangles of a country guitar picker and the rhythmic slaps of a gulping bass. So audacious a racial cocktail for 1954 that Moore nervously joked, ‘They’ll run us out of town.’ The following night divine inspiration struck again, this time accelerating a frantic black R&B spin on a white country tune, Bill Monroe’s ‘Blue Moon Of Kentucky’. Phillips was elated. ‘Hell, that’s different,’ he gasped. ‘That’s a pop song!’

Sun Records 209. ‘That’s All Right’ b/w ‘Blue Moon Of Kentucky’. By ‘Elvis Presley, Scotty and Bill.’ The big bang in the singularity of that which the twentieth-century would come to know as rock ’n’ roll.

IN MEMPHIS, ELVIS’S fame was instant. Three nights after the spontaneous recording of ‘That’s All Right’, local radio DJ Dewey ‘Daddy-O’ Phillips was playing a pre-release acetate on repeat, inciting so many requests he called Elvis to the station for his first live on air interview. The incredulous listeners of station WHBQ realised the voice they’d heard was that of a white kid.

The trio returned to Sun the following month, Elvis revealing a little more of his unearthly vocal prowess on the Rodgers and Hart standard ‘Blue Moon’: warped through his supernatural larynx to become a human distress signal ripping through the depths of the cosmos, a sub-zero shiver of solitude begging for an alien embrace to be told ‘you’re not alone’. In concert Scotty Moore and Bill Black now became his ‘Blue Moon Boys’. To the Southern audiences who first witnessed them in the late summer of 1954 they may as well have come from space. It wasn’t just the music, still blithely skipping over an unclassifiable minefield of ‘race’ and ‘folk’, ‘blues’ and ‘pop’, but the spectacle of Elvis himself, a knee-juddering, hip-wiggling, quiff-flouncing, lip-curling, nerves-a-jangling, ‘mama’-yodelling tremble of flesh and trousers.

The shocking vision of Elvis Presley, the body, generated a new evolutionary swoon. A complete desertion of the female senses. A benign adolescent barbarism. A hitherto unseen sexual transfixion. An unquenchable desire to celebrate the absolute ‘now’-ness of being alive. After Elvis, the Starman’s only expressway to humanity was blindingly obvious. Not theatre, not the symphony, not literature, not poetry, not painting, not the cinema screen. Only pop music. Loud, screaming, seat-ripping, loin-bubbling, rib-breaking, heart-dissolving pop music in all its inscrutable ecstasy.

In May 1955 the ecstasy of Elvis turned to anarchy when the crowd of the Gator Bowl in Jacksonville, Florida started a riot. It was his own fault. ‘Girls,’ Elvis announced, ‘I’ll see you all backstage.’ The majority of the 14,000 shrieking micro-boppers took him literally. By the time he’d managed to barricade himself in the dressing room they’d torn strips from his jacket and shirt and relieved him of his belt, socks and boots. Guarded by three policemen, the girls continued to pour through an open window like a plague of zombies. When Elvis finally escaped he found his car comprehensively vandalised by the scars of desire: names and numbers scratched into the metalwork and blinding the windscreen in thick smears of lipstick. Such things happened in Florida. A state in America. A cinema restaurant in Tunbridge Wells. Where hips drive kids to riot. Where starry genes collide.

And where pop music blossoms from despair.

The headline in The Miami Herald read ‘DO YOU KNOW THIS MAN?’ The accompanying photo was that of a corpse. He’d jumped from the window of his hotel room having deliberately destroyed all means of identification. The only clue he left was a handwritten note. ‘I walk a lonely street.’

The story caught the attention of Tommy Durden, a singer–songwriter in Gainesville, who saw in its ‘lonely street’ the nucleus of, as he’d describe it, ‘a good blues’. Durden took the idea to his friend Mae Axton, a fellow country songwriter in Jacksonville who’d witnessed the Gator Bowl riot first hand. She’d been there in the dressing room with Colonel Tom Parker, the manager who would soon steer Elvis’s career to unchartered agonies of exploitation. It took Durden and Axton no more than half an hour to concoct ‘Heartbreak Hotel’.

Sam Phillips had always imagined a billion dollar price tag on any white man who ‘had the negro sound and the negro feel’. When he finally found one, he sold him for $35,000 plus an extra $5000 in back royalties. After five records for Sun, Elvis was bought by RCA Victor. The label that created the 45 r.p.m. single and the promised land of Ziggy Stardust.

His debut for RCA was to do for America and the western hemisphere what ‘That’s All Right’ had already done for Memphis and the South. The big bang may have already happened on Sun, but in the eyes and ears of the world rock ’n’ roll wasn’t properly born until January 1956 with the erotic, ‘baby’-bereft pine of a quivering 21-year-old so lonely he could die. RCA Victor 47-6420. ‘Heartbreak Hotel’, by Elvis Presley.

Rock ’n’ roll born from suicide.

ACROSS THE ATLANTIC, the new ration-free England of Anthony Eden, Jimmy Porter and the ghost of Ruth Ellis groped in the post-war darkness for dizzying rhythmic thrills of its own. For the time being it had to contend with the cupped-trumpet honk of trad-jazz, the washboard ricochet of skiffle and the chubby jive of a 30-year-old former American country singer in bowtie, plaid tux and kiss-curl called Bill Haley. Technically ‘Rock Around The Clock’ was, according to its label, a ‘foxtrot’, but when Haley and his Comets took it to number one in November 1955 it pumped a deluge of cement in the foundations of Anglo rock ’n’ roll. The following April, readers of the Daily Mirror were forewarned of another ‘Rock Age

Idol’ fast heading to their shores by histrionic Hollywood correspondent Lionel Crane. ‘I have just escaped from a hurricane called Elvis Presley!’ The perfect storm of ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ blasted into the UK charts a few weeks later. The alien had landed, not from Mars but from Memphis. Britain readily surrendered.

As Mirror readers braced themselves for Hurricane Pelvis and the anthem of Lonely Street, on London’s Old Compton Street two entrepreneurial Australian wrestlers took over the lease of a split-level coffee bar. They kept the name of its previous owners, two brothers surnamed Irani: The 2 I’s. Cheaper than most of its espresso-steaming Soho rivals, the new 2 I’s began to attract idle teenagers looking for a basement hideaway to spend a few hours sipping on a single Coca-Cola, tapping the Formica to the latest skiffle and rock ’n’ roll on the café jukebox, sometimes strumming a guitar and singing along, distorting their Thames-water vowels as best they could to an exotic Southern hillbilly twang.

Among them was a 19-year-old Bermondsey boy fresh from the merchant navy where he’d been hypnotised by one of Elvis’s first US television appearances while on shore leave in New York. Tommy Hicks looked less like a rock ’n’ roller than he did a Dickensian street urchin; a sweep’s brush of hair atop a farthing-charming grin forever threatening to chuckle ‘gor blimey!’ But in the easily excited atmosphere of the 2 I’s basement, Hicks’ barrow boy approximation of The Memphis Flash struck a chord of awed admiration among his tea-chest-bass-plucking peers.

By late September, Hicks had been snatched from the 2 I’s by Decca Records, renamed Tommy Steele and frogmarched into their West Hampstead studios to record his debut single, ‘Rock With The Caveman’. Possibly intended as a pithy Darwinian thesis on the primeval origins of rock ’n’ roll: ‘The British museum’s got my head/Most unfortunate ’cause I ain’t dead.’ Or possibly not. Either way it booted Steele high up the top 20. Britain’s first born and bred rock ’n’ roll star. ‘The English Elvis Presley.’

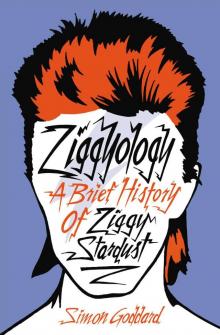

Ziggyology

Ziggyology